Reusing Rainwater and Greywater

There are high-tech ways of capturing and reusing rainwater and greywater (the wastewater from showers & sinks) in place of mains water. However, the best options are simple and low cost – such as garden watering or irrigation.

You may want to use captured rainwater within your home. However, systems to enable this can be expensive. They may not save any money, and could also have a high environment impact. It’s therefore important to look carefully at the design and operation of any system for reusing rainwater and greywater. A complicated system may not be an effective way to reduce your environmental impact.

The vast majority of the carbon emissions related to UK domestic water use are from the energy used to heat water in the home. So the first measure should always be to minimise hot water use – for example with a water-efficient shower and taps. Look also at overall water efficiency measures, such as a low-flush toilet. And then look at how to heat water using renewable energy.

In other countries the comparison between mains water and alternatives can be quite different. For example, in Germany their principal groundwater sources are very dirty and require expensive treatment. A technology that is effective in one country’s situation may not be as effective in the UK.

How can I collect and use rainwater?

In the UK, the best way for most householders to make use of rainwater is with a large water butt on your down-pipe. You can then just save the water for use in the garden, and perhaps also bike or car washing.

The equipment for this costs tens of pounds, rather than the thousands needed for a more complicated system. A complete water butt kit will include a diverter pipe to fit to your down-pipe and prevent overflowing, and a stand to allow easy access to the tap.

Can I flush my toilet with rainwater?

If you have a small garden but a large roof you may be considering a system to collect water for your toilet or washing machine. However, it’s worth looking into this quite carefully as such a system will not necessarily be financially or environmentally beneficial.

The impacts include manufacture & installation (e.g. with concrete backfill) of the tank, energy use, and periodic pump replacement. Systems often cost thousands of pounds to install, but may save only a few tens of pounds per year.

Academic studies have found that the benefits of systems for using rainwater within a house are often outweighed by the environmental impacts. In a rural area, a composting toilet could be a more sustainable way to reduce domestic water use. Rainwater harvesting is most effective when integrated into new developments, especially larger buildings. For example a school or commercial building that has a big roof area and a high non-potable water demand.

If you’re building a new home in an isolated area without mains water or drainage, and your main water source is insufficient for anything other than drinking, cooking and washing, then a composting toilet would be a better way to reduce water use.

Can I store and use grey water from my bathroom and kitchen?

Grey water is the water from sinks, baths, washing machines and so on. It’s already been in contact with us humans and our germs so storing it requires treatment, or it will quickly start to smell. The most suitable use for grey water is therefore direct garden irrigation, without long-term storage. Reducing the pollutants in grey water makes it more suitable for garden use.

Shower or bath water is easy to reuse for irrigation as shampoos and soaps are fairly mild and well diluted. Simple kits can enable you to divert grey water from your down-pipe, if this is easily accessible.

If you wish to irrigate with water from a washing machine then use a low-sodium detergent, because sodium damages plants and degrades soil (liquid detergents usually contain less salt than powders). Avoid phosphorus as well, because this causes algal blooms if it collects in ponds or rivers. Otherwise, the water has only very small and well diluted quantities of pathogens or grease and therefore these should not be of concern.

Ex-kitchen water can be very dirty – containing oil, grease, and chemicals. Because you will only have a small amount of this anyway, it may be best to avoid reusing it.

It’s important to first reduce the amount of grey water you produce. The energy used to heat water leads to far higher carbon emissions than the small amount of energy needed to treat and deliver mains water to a house. So using hot water efficiently is very important – for example, fitting spray-head taps and a low flow shower head will make a big difference to water consumption and energy use.

What’s the impact of treating and storing grey water?

Grey water contains bacteria and a nutrient source and is often discharged warm, giving an ideal situation for pathogens to multiply. Commercial grey water recycling systems use disinfectants that are often very energy intensive to produce. These additives may also cause problems if you have a private sewage treatment system.

Independent studies of systems that treat grey water for reuse in the home have found that their environmental impact outweighs any benefits. Also, with running costs higher than using a UK mains water supply, they don’t save money either. Given the equipment and disinfectant we find it difficult to see these systems as environmentally friendly for individual households. This may change as technologies are improved. In other countries they may well be more beneficial than they are in the UK.

Further Information

The book Choosing Ecological Water Supply and Treatment is mainly about private water supplies. However, it also includes detailed chapters on reusing rainwater and greywater. For example it included detailed advice on setting up a grey water irrigation system.

Related Questions

How much rainwater could I collect?For the calculation below, the roof area is the flat area of ground covered by the roof – not the pitched area. Average rainfall figures for many UK locations are available from the Meteorological Office. Suppliers should be able to give estimates for system efficiency (for example a ‘WISY’ filter is 90% efficient). The run-off coefficient of a pitched, tiled roof is 0.75, but a flat roof is 0.5 or less becuase more is lost to evaporation. You also need to check that your roof is clean.

Annual collection in litres = Roof area (in square metres) x Annual rainfall (in mm) x System efficiency x Run-off coefficient of roof

A tank would normally be sized to store 5% of the annual collection. This keep the tank fuller most of the time, which prevents stagnation. 1000 litres is equal to 1 cubic metre (m³). Water should enter the storage tank just above the bottom so it doesn’t disturb sediment collecting there. Draw water from below the surface using a submersible pump to avoid picking up pollen or other floating debris.

A filter that is 90% efficient when clean can drop to below 30% if algal growth blocks the holes in the mesh, so they need to be in a position where they can be accessed and cleaned occasionally.

A basic water butt to collect water for the garden should be very low cost, and they are sometimes deals available from your water company.

A rainwater harvesting (RWH) system providing toilet flushing for a 3 or 4 bedroom house is likely to cost about £3,000 if professionally installed. Costs for retrofitting systems will generally be higher than for those built into new houses. It may be possible to put in a simpler gravity-fed system (e.g. for a ground-floor toilet) for much less.

You also need to factor in annual checks of the system. Some of these may need to be done by a professional, such as checking the tank for leaks & debris, the pump for corrosion, or the controls & sensors for accuracy.

The payback time can be very long, and some systems may never recover costs if the parts need replacing before savings are realised. Dr Judith Thornton, water treatment expert and author of CAT’s ‘Choosing Ecological Water Treatment’ book, has researched this area for many years. She writes:

“…in general they wil not decrease your sewage charge. In rough terms therefore, given an average UK bill (metered users) of around £330 per year (for water and sewage), and likely water savings of around 20-30%, the system might save you £30 per year, and that is before you account for any maintenance or capital costs. A comprehensive PhD study that modelled several thousand different configurations of system demonstrated that mains water would need to cost more than £10 per cubic metre before RWH systems made financial sense. Regional differences in rainfall and water bills mean that rainwater harvesting systems may be economically viable in some instances (for example in the south-west of England), but do your own calculations rather than relying on those from RWH system suppliers.”

Where rainwater harvesting for toilet flushing is appropriate (e.g. in a larger building), choose the equipment carefully to minimise environmental impacts.

To minimise the environmental impact of one of these systems the book recommends a polyethylene tank rather than fibreglass. The tank should be a type that does not need concrete backfilling when installed.

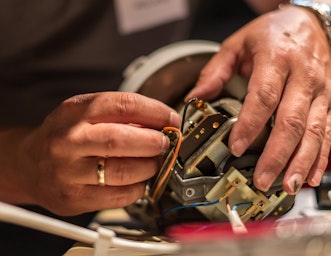

Pay careful attention to the energy demand of pumps and other components, and also to the durability of these. Choose an efficient, low wattage pump that is well-suited to the head & flow required.

Good controls will enable you to see how the system is performing. For example how much mains water backup is used, and how much water is in the tank at different times of year. It’s probably worth metering both rainwater input and mains backup.

In the UK, treating rainwater to a high standard for bathing or drinking is not recommended. Besides the expense, the impact of all the equipment needed outweighs the environmental benefits of reducing mains water use. Small-scale water treatment systems use lots of energy in manufacture and use, and the filters need to be regularly replaced, creating waste.

Even systems for using rainwater for non-potable uses within a house have quite a high environmental impact.

If you are not on mains water then collecting and treating rainwater is an option – but in the UK, groundwater or a stream will usually be more reliable and need less treatment.

Treating rainwater to a higher level is more suitable in dry countries (e.g. Australia), or places with very dirty groundwater (e.g. Germany). In these cases, the extra expense and energy use might be justifiable against the alternatives.

Please note that if you are not on mains sewerage, the Environment Agency may require that all grey and black water can be treated through your septic tank or similar system. This means you might not be able to save by putting in a smaller system.

Household ‘grey water’ (from showers and sinks ) is generally quite diluted and in some cases can just be used to irrigate a garden. Otherwise, the effective dispersal of grey water depends on soil porosity. You need to disperse it into the ground over as wide an area as is necessary to ensure you don’t have any surface water. For example by using a drainage field.

Where soil porosity is very poor, you’d need to clean the grey water before discharging it, possibly using a gravel filled tank such as a horizontal flow or subsurface bed. You’ll need some kind of trap at the front end of the system that will catch any solids, because hair is particularly likely to block things up and cause problems. You may also need a surge tank, depending on how much the flow rate varies.

For a simpler and lower cost option than a drainage field or a reed bed you might be able to consider a willow bank or a trench arch.

A willow bank is essentially a pile of bark peelings or wood shavings at least 1.5 metres deep and with a surface area of 5 to 10 square metres. It’s retained in some sort of frame, which can be a ‘living structure’ made from willow. Grey water is piped onto the middle of the pile. The solid matter is filtered out and humifies, while liquids will drain through and break the wood shavings down into a compost, which will itself be a good water-cleaning medium. The water emerging from the bottom will feed the surrounding willows. The willows need annual pruning, and wood shavings will need to be added less often.

A trench arch is like an elongated soakaway. It is a long gravel-lined trench capped with paving stones that can be pulled up for inspection or maintenance, or a row of pipes cut longitudinally in half. Raw greywater can rush along it until it finds somewhere nice to settle into. Worms and micro-organisms deal with solid matter and soon create a nice composty medium which treats the water very well.

Related Pages

Related events

Introduction to Renewables for Households

13th September 2025

Renewables for Households: Insulation

8th November 2025

Renewables for Households: Wind Turbines

10th January 2026Study at CAT: Our Postgraduate Courses

Related news

Bobbing along – the songbird that swims

10th March 2021

The joys of compost toilets

10th October 2019

Eye in the Sky

31st May 2019

Make do and mend

25th May 2019Related Books

Did you know we are a Charity?

If you have found our Free Information Service useful, why not read more about ways you can support CAT, or make a donation.

Email Sign Up

Keep up to date with all the latest activities, events and online resources by signing up to our emails and following us on social media. And if you'd like to get involved and support our work, we'd love to welcome you as a CAT member.