Energy saving at home

Domestic energy saving measures are vital if we are to achieve the goal of a zero carbon future. Reducing the UK’s energy demand will make it much easier to meet the remaining energy need with renewable energy.

The energy we use in all our homes leads to about a quarter of the UK’s carbon emissions. In an average home, with a gas or oil boiler, space and water heating will probably make up than half of your energy bill. The rest of the bill is electricity use for appliances and lighting (plus sometimes a little gas for cooking).

Because the UK electricity supply now includes lots of wind and solar power, carbon emissions from average electricity use are far lower than from fossil fuel boilers. If you pay about half your bill for gas and half for electricity, then your carbon emissions will be about 80-85% from gas use and only 15-20% from electricity use. Therefore reducing heating needs will give the biggest carbon saving.

It’s more important to reduce energy use than to generate your own renewable energy. From the very earliest days of CAT, we focused on getting our buildings to high levels of insulation and draught-proofing.

Getting started on energy saving

If you have a lump sum to invest, see our advice about getting a whole house eco-retrofit, to get you home really well-insulated and zero carbon ready. If you can’t afford that level of refurbishment, there are still many low-cost measures you can take, and I run through these below. There might also be some funding available to help you make bigger savings.

All bought or rented houses must have an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC). This shows levels of insulation, heating controls, lighting, and so on, and should be a good starting point for identifying improvements. Some energy saving measures are very cheap but will make a big difference. If you rent your home, many of these simple measures are still possible.

To reduce heating needs, measures include:

- Improve insulation – and see what grant support you could get for this.

- Draught-proof windows and doors (but check you still have enough ventilation).

- Get good, easy to use heating controls, including thermostats & radiator valves.

- Get to know your smart meter to see how it can help you save energy.

- Bleed radiators to reduce cold spots.

- Insulate your hot water cylinder.

- Shower rather than bath – and try to keep below 5 minutes!

- Fit a water efficient shower head and a hot tap aerator (check what’s on offer from your water company).

- Upgrade your heating system – there may well be grants to help you with this.

And to reduce electricity use:

- Switch off electronic appliances at the plug instead of leaving them on standby (unless needed for timed recording).

- Turn off lights when you leave a room.

- Replace old bulbs with efficient LEDs.

- Wash clothes at 30 degrees C (when possible).

- When possible, dry outdoors instead of using a tumble dryer.

- Only boil what you need in the kettle.

- Fill the dishwasher before running it.

It’s important to switch to an electricity supplier that uses only renewable sources like solar, wind and hydro power, because this helps to promote these technologies and reduce carbon emissions. However, we all still need to reduce electricity use, to help the entire grid get to 100% renewable electricity more quickly.

Read on for more advice, including the related questions below.

Insulation

You should combine insulation measures with careful attention to draught-proofing and to providing appropriate ventilation. When done properly these measures should also address damp and condensation problems – making your home more comfortable and healthier as well as reducing bills.

Here’s a quick summary – see the related questions below for more detail on each option. In addition, wrap hot water pipes in insulating foam sleeves and ensure a hot water cylinder has a cosy jacket.

In many cases loft insulation is a DIY job, with the cost repaid within a few years of savings. Getting up to about 300mm of woolly insulation meets current standards, but you could add more. Certain types of plastic foam insulation are thinner but have a higher environmental impact. For insulation in a pitched roof or flat roof you’re likely to need professional help.

For homes with cavity walls, blowing in insulation should take less than a day and cause little disruption. It should cost a few hundred pounds, which you’ll save this on bills within 3 or 4 years. However, if your home is exposed to wind driven rain you may need to be more cautious about insulating cavity walls.

If your home has solid walls, insulating these is more expensive and disruptive. To get to zero carbon we will need to insulate these older homes, and support is available for some. For lots more advice see our pages on external and internal wall insulation.

In a suspended ground floor, aim for about 200mm of insulation between the floor joists, added either from below or by lifting the floorboards. For solid floors you may need less insulation but it’s usually more work. You can either dig out the existing floor or raise the floor level (and reduce door sizes).

Draught-proofing

Draughts occur around window & door frames, through letterboxes & cat flaps, down chimneys, at skirting boards, between floorboards, and where services enter. Even very small draughts can make a room uncomfortable in cold weather and have a big impact on heating bills.

There are many low-cost DIY measures that both homeowners and tenants can take to reduce draughts. It’s important to avoid blocking any intentional vents. These include wall vents where the room has a fire or stove, trickle vents on windows, and underfloor airbricks. See the related questions below for more.

For a higher level whole house eco-retrofit to a zero carbon ready standard, a much more careful approach to airtightness and ventilation will be needed.

Windows and doors

If you need to replace windows, the most efficient are argon-filled with low emissivity (low-E) glass. Argon gas between the panes improves performance because argon doesn’t conduct heat as well as air. Low-E glass has a coating inside the gap to reflect heat back into your house. Existing windows can also be improved with secondary glazing – anything from a clear plastic film to a second window fitted inside. See our page on windows for more advice.

New outer doors are usually insulated to meet the current minimum standard. It’s important for a new door to be well-fitted and the frame to be draught-proofed. You’d need an external grade door between a conservatory and a heated room. You must leave a conservatory unheated and close it off in cold weather – see the related question below for more.

Choosing and controlling heating

Good quality controls are vital for maximising the efficiency of your heating, to control where and when you need heat and to avoid over-heating. With a boiler you usually need a room thermostat, timer/programmer, boiler & cylinder thermostats and thermostatic radiator valves (TRVs).

If your boiler is old, it should be worth considering a heat pump as a much lower carbon alternative to a new boiler. Or for an old and rural house, with restricted insulation options, modern biomass heating might be appropriate. There are grants for these low carbon options.

There are other heating options that we don’t see as a good choice – such as direct electric heating or hydrogen ready boilers. This is because of higher running costs and impacts from the greater infrastructure needed to supply them with energy. See the related questions below for more.

Cooking

On your hob, use saucepans that cover the ring or flame and have well-fitting lids. Steaming vegetables uses less energy and water than boiling and retains more vitamins. Otherwise, boil in as little water as possible to prevent vitamins leaching from vegetables. If you’re looking for a new one, then an induction hob is the most efficient type.

Grilling food is usually more efficient than oven baking. Plan your oven cooking so you don’t roast empty shelves!

Microwaves are more efficient than a standard oven, as they heat only the food and not the surroundings. However, avoid having lots of frozen, microwaveable ready meals, as the processing and storage involved in these will result in high carbon emissions.

Heat only the water you need in the kettle. Regularly boiling water that won’t be used adds up to a massive waste of energy across the UK.

Lighting and electrical appliances

LEDs (light-emitting diode) are now available in a wide range of colour temperatures and light outputs. Choosing the right type of fitting is also important for efficient use of lights. For example good ‘task lighting’ in key areas (e.g. worktops, reading lamps) so you don’t need strong lights in the whole room. Softer, diffuse lighting will suit other places. And remember to switch off lights when you leave a room!

Fridges and freezers can make up a fair proportion of your electricity bill because they’re always plugged in. Modern ones are far more efficient, so consider upgrading if your appliances are old – the savings could quickly recoup the purchase cost.

Use the low temperature setting on your washing machine whenever you can, and always wash a full load. Combine items that can need a hotter wash (like towels or bedding) into one load, so that all other washes can be cooler. Dry clothes outdoors whenever you can because a tumble-dryer uses a lot of energy.

See the related questions below for more tips on efficient appliances.

With the rise of wide-screen TVs, computers and home entertainment systems, electricity use in this area has grown, even though appliances are more efficient. Check the electricity consumption when making purchases. The average home spends tens of pounds each year just powering devices on standby, so this is an easy saving. Watch out also for ‘phantom loads’ – when an appliance has an internal transformer that draws power when the device is off but the supply at the wall socket is still on. A smart meter or similar device can help identify these.

Grants and Funding

To find out more about other funding that you may be able to claim for energy saving measures, check with your local authority or your energy company. Some support comes through the ECO scheme (‘Energy Company Obligation’) and some is from government funding delivered by local schemes.

In summer 2023, the Great British Insulation Scheme started. This provides funding for people on higher incomes who live in houses without good insulation levels. it will usually cover one main insulation measure.

The ECO4 funding is generally for households with a gross annual income less than about £30,000 who own or privately rent a house with an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of D or worse. However, it can also apply to people on higher incomes but with health issues, those claiming certain government benefits, or those meeting other criteria. It can fund insulation, heating and even solar panels. There’s some useful information about qualifying for ECO4 funding on the Ofgem website.

If you need to check your home’s EPC, use the government’s online EPC register.

In Wales you can ask Nyth/Nest scheme (0808 808 2244) and your local council or Warm Wales about energy grants for households. North of the border, Home Energy Scotland (0808 808 2282) provide interest-free loans with additional cashback offers across a range of energy saving and renewable energy measures. In Northern Ireland ask NI Energy Advice (0800 111 4455).

For further tips see the Energy Saving Trust website and the Government’s online service to find ways to save energy in your home. If you live in a old house, see the advice from Historic England on Energy Efficiency and Your Home.

Further information and advice

CAT offers many short courses, including our long-running eco-refurbishment course. See also this blog post about eco-refurbishments by our course tutor, Nick Parsons.

Joining a local energy group is often a good way to get some practical advice and feedback. Or you may have a local energy agency that can help with a basic home survey.

Related Questions

What draught-proofing measures should I take?For basic measures, checking around the house on a windy day is a good way to locate draughts. You must not block intentional vents such as wall vents (especially for rooms with a fire or stove), trickle vents on windows, and underfloor airbricks.

Wiper and compression seals are readily available for use on opening windows, external door frames and loft hatch. Foam types are cheaper but tend to wear out more quickly. Draught-proofing strips come in many types and thicknesses – so to choose the right one you need good measurements of the gaps you need to fill.

At the bottom of external doors you could add a batten along the bottom with a rubber flange or a strip of brushing. Internal doors to unheated rooms could have the same – or just use a draught-excluder.

Sash windows can be tricky – a brush seal may work, but some sort of secondary glazing will be better. See our page on windows for more.

Thick, well-fitting curtains will greatly reduce night-time heat loss from windows. Make sure curtains finish on a shelf above a radiator rather than hanging in front.

For letterboxes and old-fashioned keyholes you can buy special cover. Either board up and insulate an unused fireplace, or add a ‘chimney balloon’ if you’re planning to use the chimney in future.

For the gaps at skirting boards, between floorboards and around service ducts you can use a filler or sealant. Check that the type of filler (e.g. mastic or caulk) is suitable for the surfaces.

For big gaps you could wedge in wooden beading or round dowels. You can trim this to shape (using a surform or other tool) and tap into position using a dab of wood glue. The added wood could be stained to match surrounding timber.

A more in-depth approach to air-tightness would involve a full test with blower door equipment. As well as measuring heat loss more precisely, this helps identify the less obvious draughts through the building fabric.

If you have cavity walls and they haven’t been insulated, up to a third of the heat produced in your home could be escaping. Insulation should reduce your heating costs and carbon emissions from your home significantly. The insulation itself needs to be suitable for the conditions inside a masonry cavity, and so choices are limited to three options: blown mineral wool, plastic beads or plastic foam.

Cavity wall insulation should cost only a few hundred pounds and recoup this installation cost within 3 or 4 years. With gas-fired heating, you’ll reduce annual carbon emissions by almost half a tonne per year. This makes it several times better than installing a solar PV roof in terms of both carbon savings per pound spent and payback time. Both costs and savings will be higher for a detached house.

The installation process must include an assessment to ensure that the construction is of a suitable type. Installers should work through an accredited scheme and guarantee the installation for 25 years. It may take about 3 hours to inject the insulating material into the cavity. For installers, see the Cavity Insulation Guarantee Agency (CIGA), National Insulation Association, or British Board of Agrément.

Some homes may be classified as ‘hard to fill’ cavities – perhaps too narrow or uneven to fill easily. Insulation may then be more expensive to install (perhaps 2 to 3 times as much), or it may not be feasible – external or internal insulation may then be better.

A Which? Magazine survey in 2011 found that some installers were not undertaking adequate assessments. According to industry guidelines, they should inspect all external walls thoroughly to check for cracks/defects, check all internal walls to check for any existing damp, and do a cavity check (with a drill hole) on all walls. A proper survey like this is likely to take an hour. Do ask a few companies around to give quotes.

Cavity wall insulation should not cause problems of dampness, but a proper assessment of the property is needed to ensure it would be suitable. If your home is towards the west coast of the UK, more prone to wind-driven rain, then it might be unsuitable for cavity insulation if it’s in a very exposed, unsheltered position and there are cracks in the external wall. For those few homes in this position, measures could taken to prevent damp risks – for example by putting extra protection in the form of boards or tiles on the exposed walls. There will be a cost to this of course, and it should be compared with quotes for options such as internal or external wall insulation.

BRE (Building Research Establishment) research in the 1990s showed that cavity wall insulation when assessed & installed properly does not lead to an increased risk of damp. The study found that the structural condition of the walls was the most important factor in damp problems – for example, badly filled mortar joints or ‘dirty cavities’ (where, during construction, mortar has dropped down inside the cavity – i.e. if too much is used). Over time, this can cause problems with damp-proofing.

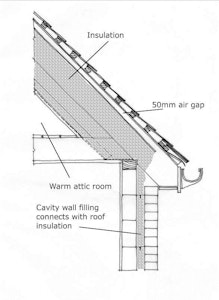

A ‘cold loft’ roof, with the insulation at ceiling level (laid flat in the floor of the loft) is generally the most economical, and easy to install. However, if you want to insulate in the slope of a roof in order to make use of the space, then here are some tips.

The most economical way of achieving a good thickness of insulation in the roof slope is to have two layers of timber, one supporting the roof finish and another supporting the insulation and ceiling finish. Batts or loose fill insulation is generally better between rafters, because it will give a tight fit. Otherwise rigid material has to be very precisely cut to fit well.

To reduce cold-bridging, timber I-Beams or I-Joists can be used when adding new beams or building a new home.

In an existing roof (with rafters supported on roof beams), the second layer of timbers (ceiling joists) can be hung off the rafters using hardboard, ply or timber ‘hangers’, or nailed crosswise to them, or they can span between the roof beams. This technique can also be used with flat roofs.

An air space of 50mm must be left between the insulation and the tiling felt, unless the felt is of a low-vapour resistance type. If using a breathable membrane, with insulation up against it, then above the membrane you would put counter battens (top to bottom) as well as the standard battens (side to side), for adequate ventilation beneath the tiles. Sometimes, a breathable membrane is used with only standard battens, with the membrane slightly draped between rafters to allow ventilation – in this case an air gap of about 25 mm would be needed between membrane and insulation.

Thin wood-fibre boards (22 or 35mm thick) can be used as an alternative to a membrane under tiles. When re-roofing, the fibre-board is laid over the rafters, and then counter battens (in line with rafters), and then standard battens to fix the tiles/slates to. Thicker wood fibre boards can also be used, to give more insulation and achieve a lower U-value (to minimise heat loss).

A ‘warm roof’ will have waterproof insulation on the outside of the structure (so the main timbers are on the warm side of the insulation). It’s a useful way of upgrading an existing roof when internal room height is at a premium. On a sloping roof, the tiling battens are supported by rigid insulation and fixed through to the rafters by special screwnail fixings. The insulation must be waterproof, such as cork, foamed glass or closed-cell plastic foam board – these will tend to be more expensive than the standard insulation materials for internal use.

You can also read more at the webpage of the Energy Saving Trust, on Greenspec’s pages about ventilated and unventilated roof insulation options, and in a guide from Historic England.

If you can access the floor from below via an unheated cellar or basement it will be easier, otherwise you’ll have to lift the floorboards (which requires care to avoid damaging them).

225mm of a renewable or mineral fibre type of insulation is a decent amount. Make sure you keep good ventilation to the underfloor space beneath the insulation – with vents at either side for air flow.

Batts or loose fill insulation is generally better between joists because it will give a tight fit. Otherwise rigid material has to be very precisely cut to fit well.

Renewable insulation will need to be protected by a breathable membrane to protect it – if the floorboards are not well sealed. See the website of the supplier of insulation you’re using (or call their advice line) for advice on the type of membrane that would be needed. Natural insulation materials include hemp, sheeps wool, recycled textiles, recycled paper (loose fill), and wood fibre.

Loose fill insulation can be carried between the joists on a membrane or netting nailed to floor joists or on a low-vapour resistance board (for example softboard, a fibreboard bonded by heat rather than glues – this is good for Warmcel insulation made from recycled newspaper).

For other insulation materials (e.g. standard mineral fibre types) it will be worth looking on the website of the manufacturer as they’ll usually have guidance sheets on how the material should be installed and what limitations there may be.

You can also see some information and examples on the Energy Saving Trust and Historic England websites.

Traditionally, solid floors were laid directly onto soil. This relies on the ground underneath being kept dry, usually by it being higher than the ground outside the building, and by having adequate drainage.

The most common method now used is to have a thick concrete slab laid on a damp-proof course (e.g. a polythene membrane). A layer of polystyrene insulation is then finished with sand/cement screed and tiles or board.

For a low-impact alternative to the above you could look into using recycled aggregate in the concrete (rather then newly quarried material), and perhaps using stabilised earth as the screed. You could also consider using recycled polythene or bitumen for the damp-proof course.

A solid floor of stabilised earth or limecrete should have a solid insulation material below it, such as cork, perlite or foamed glass, with recycled polythene vapour check and damp-proof membrane (DPM) below this.

Try to achieve at least 150mm of insulation for a solid floor. Insulation should be placed around the edge of the floor, and the floor finish supported on some sort of rigid insulation. Possible materials include cork, perlite (volcanic glass), lightweight expanded clay aggregate (‘Leca’), foamed glass (slabs or granules), fibreboard, mineral wool boards, or plastic foam of some sort. A vapour check layer will normally be required to prevent condensation occurring within the insulation layer.

Another possibility is a hemp & lime (or ‘hempcrete’) floor. Lime has a much lower environmental impact than cement, so if you can use it place of cement in mortars or concrete you will be reducing the ’embodied energy’ of the floor and the carbon emissions from construction. The hemp provides the insulation. See for example the details of how we insulated the WISE building at CAT.

If you are redoing a floor, then you may have the chance to consider underfloor heating. Because it runs at a much lower temperature than standard radiators, wet underfloor heating is more efficient and provides a more comfortable type of heat. It’s particularly appropriate for use with heat pumps, as these need to supply low-temperature water to run efficiently.

You can also see some information and examples on the Energy Saving Trust and Historic England websites.

The first two of the following four methods involve adding insulation to the outside of the roof, so will be suitable if there is little headroom underneath, or if access is difficult. The second two involve adding insulation underneath the roof. If insulating on top of a flat roof, make sure that it still drains well so that water does not pool on top.

Upside Down or Inverted Roof

An ‘upside down’ roof uses waterproof insulation on the outside of the building structure. The insulation is laid over the existing waterproof membrane and held down with something – which could be pebbles, turf (for a green roof), paving slabs, etc. Suitable insulation materials will tend to be a bit more expensive, and include cork, foamed glass and closed-cell plastic foam. You’ll need to check that the structure can bear the weight of the insulation and finish. This option keeps the existing membrane, but there is a risk that water will percolate through the insulation and so cool down the roof deck – causing condensation.

Warm Roof

A warm roof will have the insulation laid over a vapour control layer (itself over the roof deck), with a membrane laid over the insulation and suitable finish on top. You’ll need to check that the structure can bear the weight of the insulation and finish. If you are replacing the roof membrane anyway, then this will be a better solution than the ‘upside down’ roof (above), as it will keep water above the insulation and so keep the roof decking warm. You could still keep the existing membrane underneath the insulation if it would be difficult to remove.

Cold Roof

The insulation is put between the roof joists. A ventilated gap needs to be retained between the top of the insulation and the roof decking, to avoid condensation build-up. It can be difficult to get adequate ventilation, so this method is often not recommended.

Internal Insulation

A method similar to dry-lining of walls can be used, with a plasterboard/insulation board added to the underside of the internal roof, below the joists.

There are basically three different types of insulation material:

- Organic – those derived from natural vegetation or similar renewable sources, which tend to require a low energy use in manufacture (a low ‘embodied energy’). Examples are sheep’s wool, cellulose, cork, wood fibre, and hemp.

- Inorganic – derived from naturally occurring minerals which are non-renewable but plentiful at source. Likely to have a higher embodied energy than organic materials. Examples are mineral/glass fibre, perlite and vermiculite (from volcanic rock) and rigid foamed glass.

- Fossil organic – derived by chemical processes from fossilised vegetation (oil) – a finite resource. Fossil organic insulation materials such as expanded polystyrene and polyisocyanurate or phenolic foam are highly processed, resulting in a high embodied energy.

Which is best?

If possible it is better to choose insulation materials that have not been heavily processed as this will reduce the carbon footprint and environmental impact of your home. But it is far better to install cheaper inorganic or fossil organic materials with the right physical properties and a low thermal conductivity than to install nothing at all.

In many cases, organic insulation material can be applied instead of inorganic or fossil organic, but there are exceptions. For example, there is not an organic insulation material suitable for cavity wall insulation.

Think also about the ease of installation. Loose fill insulation is quick to put in in lofts, but cannot be DIY installed in anything other than a flat place. Rigid boards and batts will come in certain sizes, but need to be cut to shape if you have some unusual spaces. Some materials can be cut with a knife, but a few will need a saw. Some mineral wool now comes in a thin foil or plastic wrap, to protect from the fibres. You should still wear a face mask when installing any type of installation, as small fibres of any kind are best not inhaled.

A conservatory can be a great way to use solar power. And as well as saving energy, it will provide a pleasant extra room. The big thing to remember is that a conservatory should never be heated – or all the benefits will be lost!

A conservatory is a ‘buffer’ against the outside weather – the temperature will stay a few degrees warmer than it is outside. For much of the year a conservatory is a very nice place to be. However, you’ll need blinds or shutters to prevent overheating in high summer. Growing seasonal vines or creepers across the roof is also a great way to get summer shading. A south-east facing conservatory is best, as it gains from the morning sun but will be slightly shaded from the westerly sun at the warmest time of day.

A conservatory can also act as a lobby for coming and going from the house, so reducing draughts and heat loss. Fresh air coming in to the house via the conservatory will be warmed on its way through. This is good, because lots of the heat loss from a well-insulated house is through ventilation.

A danger with conservatories is that they come to be relied upon as an extra living space in the home. As the coldest months come around, a few degrees above outdoor temperatures is still quite chilly. This leads to the temptation of putting a heater or radiator in, a move that would make your home an energy guzzler! It is impossible to insulate such a highly glazed room sufficiently,so if you want to maintain energy and monetary savings, you’ll need to resist temptation and keep it unheated.

Shutting the conservatory off from the main part of the house with solid doors, or glass doors with thick curtains, will stop heat escaping at the coldest times of the year. Plenty of ‘thermal mass’ within the conservatory will store the heat gained for longer. So if it is being added to an existing brick wall, much of this could be kept for this purpose. Alternatively, a solid stone or brick floor will soak up and then slowly release heat as the evening cools down.

For a sunny but heated space in your home, consider instead a sun-room. This would have double glazing throughout with an insulated solid roof and well-insulated curtains or blinds. An insulated, heated sunroom would need to meet Building Regulations, so the balance of windows and insulated roof or walls would need to be designed carefully.

A conservatory may seem cheaper to build than a proper extension, but this is not always the case – they can be more costly per square metre than the rest of the house. And if it ends up as a heated room then the less obvious heating costs will not be at all cheap!

Condensation is due to excessive moisture, cold conditions, cold surfaces or inadequate ventilation. It can cause mould, heat loss and building damage. To address these issues, the room should be properly insulated and adequately heated (to keep the surfaces warm).

So do take all feasible insulation and draught-proofing options, and look into improving single glazing with either replacement glazing or with secondary glazing (a cheaper option).

Condensation may still occur on replacement windows, as they’ll still be the coolest surface. New windows will be more airtight than old ones, so warm moist air will be no longer be escaping through cracks in the frame and around the seals. This means that existing damp issues may become more pronounced. Many windows will include trickle vents in the frame, to allow a small amount of ventilation, but to keep the house warm and dry you may need to take a few other measures to avoid producing lots of moist air.

Drying clothes indoors can easily cause problems of damp and condensation, leading perhaps to mould, etc. So if you need to dry indoors, it should be in a room that can be shut off and ventilated (perhaps with heat recovery, as mentioned below).

The bathroom and kitchen in particular should be able to be ventilated in a controllable way, to stop moist air circulating into the rest of the house. For example, after a shower or bath, leave the bathroom door shut and the window open for a while until moist air & condensation on the window/mirror has cleared. Do the same when cooking if you can; if your home has an open plan layout at least stop the moist air circulation where possible (e.g. to the upstairs rooms).

To avoid heat loss from a room like a kitchen or bathroom, where lots of moist air is regularly produced, you could consider a heat recovery extractor fan. It may be worth getting a slightly bigger heat-recovery fan unit than you need, as they can be a bit noisy if they are operating on full power. This may be fine if are just switching it on for a short while to clear the bathroom, but it could be obtrusive in the kitchen. If a fan unit is not supplied with more solid covers over the plastic slatting, it could be worth fitting something if you live in a house that is a bit exposed to the wind (as they could let in draughts when not in use). An openable wooden casing could be fitted quite easily.

If drying clothes indoors is not an issue, and you’re already careful about venting away moisture from bathroom & kitchen, then excessive condensation may be from some other cause, such as a water leak somewhere (e.g. from a pipe under the floor or in the loft), or water penetrating the structure from outside (such as rainwater coming in cracks in masonry, or if gutters are broken). If problems persist, it would be worth investigating these issues, as over time they’ll cause damage to the building.

The U-value is a measure of how many watts (representing the rate of flow of energy) pass through one square metre (m²) of a construction detail (such as a wall) for every degree difference in temperature between the inside and the outside. Temperature is measured in kelvin, and 1K = 1°C (degree centigrade).

As an example, a U-value of 6.0W/m²K for a single glazed window means that six watts will be escaping through each square metre of glass when the temperature difference is one degree. If it is 20°C in the house and 0°C outside, then the heat loss is 20 x 6 = 120 watts per square metre.

U-values are generally used to describe the thermal performance (heat loss) for a section of construction that involves several materials – such as a wall made up of timber, insulation, board & render.

Thermal conductivity

For individual materials, such as a type of insulation, you’ll come across the term ‘thermal conductivity’, also known as a k-value or λ-value (lambda). This is the rate at which heat flows through a particular material, and good insulation will have a low thermal conductivity. It is measured in watts (heat flow) per metre (depth of material) per degree difference (inside to outside), so the unit is W/mK.

Most natural insulation materials (hemp, wool, recycled paper or textile) will have a thermal conductivity of about 0.035 to 0.040 W/mK, which is similar to the performance of conventional mineral wool insulation. Foil-backed plastic foam insulation boards are slightly better, with thermal conductivity about 0.023 W/mK. So about 100mm of the plastic foam board will give equivalent insulation value to about 150mm of the various woolly types.

There’s currently a fair amount of promotion of ‘hydrogen-ready’ boilers, which seems to be led by the fossil fuel industry. Note that gas boilers have been required to be able to burn a blend with about 20% hydrogen since the 1990s. Therefore in almost all cases there’s no need to change a boiler to be ready for only a blend of hydrogen into the gas mains (if that were to happen in future).

In terms of moving to 100% hydrogen, there are some potential issues. Making hydrogen from electricity is even less efficient than direct electric heating (which is already a poor choice). One unit of electricity will give only 0.6 units of heat, based on hydrogen generation being 70% efficient and the boiler 90% efficient. Overall, a heat pump would then be 5 or 6 times as efficient as a hydrogen-burning boiler.

Also, the main industry proposal is to make hydrogen from fossil fuel (natural gas) and use some not yet proven way of capturing and storing the emitted carbon. There are big questions about how this will be achieved and how much the hydrogen will then cost.

Direct electric heating, such as electric wall heaters or an electric boiler, will not usually be a good choice for heating a house.

This is because direct electric options give only one unit of heat for each unit of electricity consumed, whereas a heat pump can give three or more units of heat for each unit of electricity it uses. Therefore the running costs of direct electric heating will be 3 or more times as much as a heat pump.

In addition, the widespread use of direct electric heating would put a very high load onto the electricity grid. This would make it much harder to build enough renewable energy generation to get to a zero carbon grid. Minimising electricity demand is therefore important, which is why heat pumps are a good option.

Fridges & freezers are always plugged in, and so can use a lot of energy over time. The efficiency of these appliances has improved hugely in the last few decade. If yoursis very old, then upgrading to a new model can recoup the purchase cost very quickly.

When buying a fridge or freezer, look carefully at the rating on the Energy Label, and choose the most efficient rating possible. Buy an appliance that is no bigger than you need, as a half-empty fridge works harder to cool down after the door has been opened.

Put a fridge or freezer in a cool room if you can – or at least away from a cooker, other heat source, or direct sunlight. Allow space around the back grill for good air circulation. To maximise efficiency keep the back grill clean from dust, replace damaged door seals and defrost if needed. Lowering the thermostat by 1 degree increases energy consumption by a few percent, so keep a fridge only as cool as you need.

Most energy use in a washing machine is for heating the water, so use a low temperature setting whenever you can and always wash a full load.

Tumble-dryers use lots of energy so use a washing line to dry clothes as often as possible. A high-speed spin cycle is an efficient way to remove water; a 500rpm spin removes about one-third of the water, but a 1100rpm spin removes half. Again, if buying a new machine look for the highest Energy Label rating. New ‘heat pump’ based tumble dryers are much more efficient, but do cost more.

Signing up for a ‘green tariff’ from a company focused only on renewable energy is a great way to support the renewable energy industry. Changing your supplier is now very easy, and in most cases won’t make any difference to your supply.

One issue is that the small companies that specialise in renewable energy may not be part of the ‘Warm Home Discount’ scheme (although if they get enough customers they will be brought into it). This scheme gives a rebate to people at risk of fuel poverty, such as those receiving Pension Credit Guarantee Credit and some others. If this applies to you then you’ll need to stay with a larger provider to get this rebate.

Which green tariff?

We recommend choosing a company that only supports renewable energy. This means your money will not indirectly go to operate or build fossil-fuel power stations.

All electricity providers are required by the government to include some electricity from renewable sources. If they just offer a green tariff as one of a range of tariffs, then they may be simply charging a premium for electricity they’re legally required to produce! This is why we recommend companies that invest your electricity bill payments only in more renewable electricity.

If enough people sign up for renewable energy tariffs with these suppliers, then demand for renewable electricity will rise above the minimum government requirement. Therefore, as well as signing up yourself, encourage others to do the same.

The Ethical Consumer website gives a ranking based on the ethical and environmental record of electricity & gas suppliers. You have to be an Ethical Consumer subscriber to see the whole report, which gives more details.

I’m on a green tariff – so can I use as much electricity as I like?

It’s important to bear in mind that signing up to such a tariff does not mean you can leave all your lights on because it’s all zero carbon! If you use more electricity through your green tariff it means that less renewable electricity is left for those that are not on green tariffs. This means that more fossil fuel will be burned to meet their share of energy use.

Also, every means of generating electricity has some environmental impact, including the energy and materials that go into manufacture and installation. Energy saving measures are vital, because it’s them much easier to meet our electricity needs with energy sources such as wind farms, and wave & tidal power. Our Zero Carbon Britain project has a lot more details about how we can meet all our energy needs using only renewable energy.

Related events

Build a Tiny House (Sold out)

13th June 2025

Zero Carbon Britain: Carbon Literacy for Communities Online

17th June 2025

Cob Building

21st June 2025Study at CAT: Our Postgraduate Courses

Related news

More solar energy for CAT

4th April 2025

CAT Conversations – Dr Frances Hill

10th July 2024

CAT Stories – Aber Food Surplus

23rd May 2024

Taking back power

9th April 2024Related Books

Want to learn more? Short Courses at CAT

31st May 2025 Short Course Grow the confidence to use basic DIY tools at home in this hands-on workshop. Learn how to use the principal tools for DIY projects at home and put these new…

Read More10th June 2025 Online Courses and Events Explore climate solutions, create an action plan for you and your work, and gain Carbon Literate certification on our online course.

Read More17th June 2025 Zero Carbon Britain Explore climate solutions, create an action plan for you and your community, and gain Carbon Literate certification on our online course.

Read More

Did you know we are a Charity?

If you have found our Free Information Service useful, why not read more about ways you can support CAT, or make a donation.

Email Sign Up

Keep up to date with all the latest activities, events and online resources by signing up to our emails and following us on social media. And if you'd like to get involved and support our work, we'd love to welcome you as a CAT member.