Wood-Fired Heating

For some homes wood-fired heating could be a good alternative to fossil fuel. Whether it makes sense for you will depend on your location, the appliance you choose, and the type of fuel.

The risk of air pollution is an important factor, and counts against using wood fuel in more urban areas. However, even with very dry wood and efficient appliances there are other limits. In the UK we don’t have enough land to grow wood fuel for more than a small proportion of homes.

In CAT’s Zero Carbon Britain report we only have a small contribution from biomass (wood fuelled) boilers. They can be useful for older rural homes that currently use oil or LPG and where adding more insulation is tricky due to planning restrictions. Wood fuel does not make as much sense in more built-up areas, especially if used in a more traditional stove.

Modern ‘batch’ log boilers and pellet-fired stoves or boilers offer you convenient and efficient ways to heat with wood fuel. Their high efficiency means that they have much cleaner levels of emissions than traditional stoves or ranges.

Before switching to any new heating system it’s vital to maximise energy efficiency through insulation and draught-proofing measures. This will allow you to choose a smaller boiler, and use less fuel to run it.

A low carbon fuel?

When burned, biomass fuels release the amount of carbon dioxide that they absorbed when growing. Therefore biomass fuel is only sustainable if more trees are planted to replace the ones being harvested.

In comparison, the carbon in our reserves of gas, oil and coal was absorbed over millions of years. We are currently releasing all this fossil carbon within the space of a few decades.

Very little energy is needed to harvest and process biomass fuels compared to their heat output. Because log fuel is bulky it really needs to be used fairly locally to be an effective option. Pellet fuel is much denser and is therefore easier to transport over longer distances.

Sustainable biomass fuels are a useful piece in the puzzle of meeting our energy needs in a zero-carbon future. They are a great way of filling in some of the gaps between other intermittent types of renewable energy. Growing fuel also creates jobs and supports local economies.

Choosing a wood-fired heating appliance

Advanced log and pellet boilers have been common for many years in mainland Europe. They are as efficient as modern gas boilers – converting about 90% of the fuel into useful heat.

A pellet boiler automatically draws the pellets from a large hopper, making them as convenient as oil or gas heating. For a smaller house, you could fill a pellet boiler-stove manually using bagged pellets. See for example our case study video. You’d still want one annual bulk delivery of pellets to keep costs down, but only a small storage space would be needed.

A ‘batch’ log boiler can be fired up less than once a day, to heat water in a large buffer cylinder (or accumulator tank). Your thermostat settings will then determine how this hot water is piped around your house.

A simple wood stove is a great improvement over an open fire (which is very poor – most of the heat goes up the chimney). However, some stoves give off much more smoke than others. The quality of the fuel and how well you operate a log stove will also have a big impact on emissions.

Combining wood fuel with either solar water heating or diverted photovoltaic output (in the summer), can give you renewably-generated hot water all year round.

No fire without smoke?

Addressing carbon emissions is one thing, but it’s important to burn wood as efficiently as possible to minimise other types of pollution.

Modern log and pellet boilers emit very low levels of particulate matter and oxides of nitrogen. Pellets have a much lower moisture content than log or woodchip – less than 10%. It is also easier to run a pellet stove or boiler at a lower output without losing efficiency.

The emissions standard met by modern automated boilers is better than is needed for use in a smoke control area. Many standalone (not water heating) log stoves can meet these less strict smoke control standards, but will still cause air pollution if not operated well.

When buying a new stove or other solid fuel appliance these will now need to meet the Ecodesign regulations for cleaner burning. If log stoves or ranges have a back boiler for heating water this tends to make it harder to burn fuel cleanly.

Logs will only burn efficiently if they have a low moisture content. Ideally this means storing for almost two years. We recommend having a carbon monoxide detector if you have a log stove, to check that the ventilation and efficiency is adequate. See the related questions below for more on using a stove efficiently.

What’s the installation cost?

The price will vary according to the specification of the boiler. For an average sized house, a basic log boiler might cost about £3,000, while one with a higher standard of controls might be £6,000. A pellet-fired boiler could cost £9,000. For the total installed cost (including flue, accumulator tank, fuel store, etc), add maybe £12,000 to £15,000 to those boiler costs.

A smaller pellet stove is perhaps a few thousand pounds. A log stove could cost between £500 and £1000, with installation costs probably the same again.

What support is available?

The modern high-efficiency appliances are expensive, but in some cases you can get a grant through the Boiler Upgrade Scheme. This covers England and Wales and replaced the previous incentive scheme in April 2022.

The Boiler Upgrade Scheme will provide £5,000 for a biomass boiler. It does not cover traditional log stoves (it does also fund heat pumps). There are some restrictions on biomass boilers – for example you must be in a rural area (a village or very small town) and have no mains gas available. Your installer will claim the grant on completion of the job, and you’ll pay them the remainder of the cost.

In Scotland or Northern Ireland try either Home Energy Scotland or NI Energy Advice to see what support is available. To find any other local grants available in the UK for energy-related measures, check with your local authority. See also the Government’s Help to Heat summary page.

Where do I find installers?

When installing wood-fired heating, it’s important to find a qualified professional installer who can properly size and design the system. It’s best to get a few quotes from different installers, to compare prices.

You must use an accredited installer to claim the Boiler Upgrade Scheme grant. There’s a searchable database of installers on the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS) website.

More generally (such as for a standalone log stove) you could use the HETAS website to find retailers and installers. In addition, some installers will have voluntarily joined other professional bodies that promote high standards.

How do wood fuel costs compare to other options?

Buying one bag of pellets at a time would be expensive. If you go for bulk delivery you could pay costs similar to or less than fossil fuels. The size of hopper will determine how much you can buy at once.

A tonne of pellets should have an energy content of about 4500kWh. That means that if you can buy a tonne of pellets for about £400, then the price per kilowatt would be about 9 pence. With a boiler efficiency of about 90%, the price per kWh of useful heat would be about 10 pence. That’s less than current high gas prices (of 11 or 12 pence after boiler efficiency), and should be less than LPG and oil.

If you divide any given price per tonne of pellets by 4000, this will give you a rough price per kWh of useful heat (with both prices in pounds).

To help with comparisons, heating oil will give just over 10kWh per litre and LPG about 7kWh per litre. Therefore if prices for each were about £1 per litre, then oil would cost about 10p per kWh and LPG about 14p per kWh. For other fuel prices you can adjust these calculations.

Bought in bulk, log fuel should be cheaper than pellets, but it will depend on your location. Logs are cheapest (and therefore make most sense) in very rural areas where there’s plenty of locally harvested fuel available. The moisture content is important when buying logs by weight, because freshly cut wood is much heavier. It will get much lighter after you store and dry it.

Beyond the price per supplied kWh, how efficiently you burn the fuel will then be important. A modern pellet or log boiler has similar efficiency to a modern oil or gas boiler. However, an older or more basic appliance (e.g. a log stove or range) will not be as efficient, so your effective heating costs will be much higher. A 90% efficient appliance uses about three-quarters as much fuel as a 75% efficient appliance.

Websites that can be helpful when seeking suppliers include HETAS/Woodsure, the UK Pellet Council, and the government’s Biomass Suppliers List.

Further information

For some additional details see our questions and answers section below.

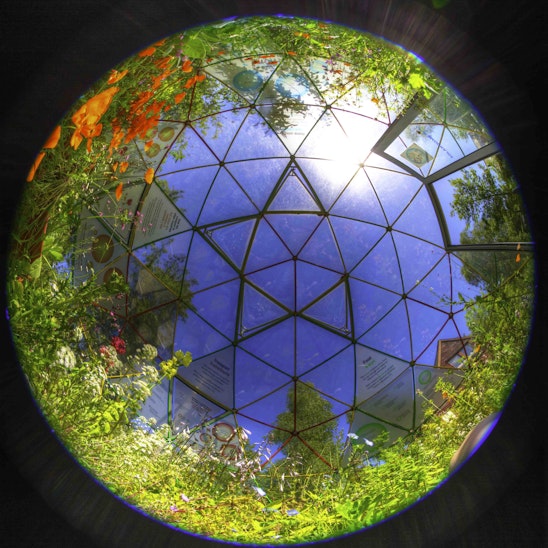

CAT has been using wood-fired heating ever since we started in the 1970s, moving over to more efficient appliances as these became available. You can come on one of our short courses to learn more.

Related Questions

How should I store log or pellet fuel?Logs should be stacked and stored in a covered but well-ventilated place for at least one year, preferably two. This is in order to air-dry the wood to a moisture content below 25 or 30%. An open-sided wood store would be suitable, a garage wouldn’t.

Bringing logs inside for the last week or so improves them to room dryness. Stoves might be specified to cope with 50% moisture content, but the efficiency will suffer – causing worse emissions.

The required storage space depends on how big and how well-insulated your home is. A small cottage is likely to need 8 cubic metres of logs each year, a 3-bedroom house 12 cubic metres, and a large detached house 16 cubic metres.

Wood pellets, made from compressed sawdust, have only about 8% moisture content. Pellets for domestic use should be to the ENplus standard. Pellets have a higher energy content than logs and take up less than half as much space. Compared to heating oil, pellets have about half the energy density so take up twice as much volume of pellets as an oil tank.

Pellets can be piped straight into a hopper, or delived in bags to store in the shed or garage. With a pellet stove using 0.5 to 1.5kg of pellets per hour, a 15kg bag should last a few days.

Larger systems, such as for a school or a block of flats, can use chipped wood. This allows more automation than logs and may be cheaper than pellets. Seasoned wood is delivered, chipped, and stored until it reaches 15% moisture content. For larger schemes, it’s a good idea to have a supply contract with a trusted supplier to ensure a reliable supply of wood.

Manually fed stoves can produce lots of pollutants if operated badly.

Logs should be burned fiercely with lots of air input until they are almost charcoal, after which the stove can be ‘damped down’. Reducing the air supply too early would create lots of smoke & tar. The key is good ‘secondary combustion’ of the high-energy volatile gases given off by burning wood.

Some stoves are fitted with a ‘Lamda’ sensor, to regulate the amount of oxygen added and optimise efficiency.

In traditional log stoves, burning green (fresh, wet) wood leads to corrosion of the liner and stove by acid, and tar coating the interior. Cast iron stoves are popular as they are less susceptible to corrosion from acid from burning damp wood. But this would still mean poor quality emissions. If you’re burning properly seasoned wood a steel stove will be fine.

Avoid burning treated, painted or glued wood, or non-wood waste, as these will give off toxic and polluting gases.

Logs need to be either bought seasoned, or stacked and stored for long enough to reach a suitable moisture content. New green logs must be stored for 2 years to dry enough.

Building regulations require all fuel burners to have a dedicated vent to avoid production of carbon monoxide. The chimney needs an insulated flue to prevent fumes condensing as tar.

With complete combustion, wood burns to a small amount of ash, which is an excellent fertiliser (unlike coal ash).

A more expensive log boiler will be made with higher-grade steel, giving a longer expected lifespan. It will have greater control over aspects such as airflow to the combustion chamber, which means it will operate more efficiently when starting up or winding down. A boiler without as much control (e.g. over air inflow), can suffer from more tar, acid and other by-products of poor combustion. These effects will shorten the life of the boiler & flue, as well as causing a lower quality of emissions.

As well as the boiler itself, the total installation cost will include an insulated flue, accumulator tank, pellet hopper (where needed), pump, controls and labour.

A properly insulated flue, needed for efficient operation of a biomass boiler, can cost around £2,000 to £2,500.

An accumulator (or buffer) tank could cost about £1 per litre. It will probably be sized to between 50 and 100 litres per rated kW for a log boiler. A pellet boiler needs a smaller accumulator, at maybe 20 litres per rated kW. This will enable you to run the pellet boiler flat-out for a longer period, to get the most efficient combustion.

If your house has underfloor heating, the buffer tank can be smaller because you only need to supply water at 30 or 35 degrees Centigrade. To supply radiators with high temperature water, the buffer tank needs to be larger, to keep enough water above 50 degrees.

A traditional type of radiant stove with a back boiler (or water jacket) to feed radiators is not usually that efficient – leading to more smoke and using more fuel. An example of the low efficiency is that almost no traditional wood burners with back boilers qualify as ‘exempt appliances’ for smoke control areas.

The new EcoDesign standards are more stringent. A few new wood-burning stoves do meet them while also producing hot water, by using better designs than a basic back boiler.

If a wood stove is not run efficiently, this increases the probability of tar condensing in the chimney, and the risks this poses. The more hot water that is required (for example if trying to supply several radiators plus a hot water cylinder), the lower the efficiency will be and the harder the stove will be to operate.

Higher efficiency appliances move the water heating stage away from the fire box, extracting heat after the gasifying stage of combustion. With this improved design (and also much better controls, for example on air inlets), modern ‘batch’ log boilers or pellet-fired appliances can produce hot water at 90% combustion efficiency, and meet stricter emission standards.

With traditional back boilers the ratio of water to space heating was not usually that good – perhaps 60/40 but often 50/50. If half the output is to space heating it can be difficult to get enough hot water without overheating your main room, so wasting fuel. Pellet stoves have a much better ratio of 80/20 or 85/15 (for water to space heating), while log or pellet boilers only produce hot water so the problem does not arise.

A more efficient standalone stove with no water jacket might be used as a supplement to either a heat pump or a log or pellet boiler in a more rural home that’s hard to insulate. Then the main heat source can be sized to meet the usual space heating demand, with the stove as top-up for occasional cold snaps.

Depending on the boiler it might possible to burn modified vegetable oil in place of heating oil, but there are both environmental and financial reasons why it’s not really an effective solution. If you currently heat your home with oil and are seeking an alternative then a heat pump or perhaps a modern wood-fired boiler is likely to be better.

One of the key issues is that the amount of liquid biofuel we can produce sustainably in the UK is very small, and can meet only a tiny proportion (less than 5%) of the transport fuel demand – let alone further demand from heating. This applies to bio-oil from crops like oil seed rape, plus the small amount of waste cooking oil available.

To meet a given energy demand requires far less land for wood fuel than it would for crops like oil seed rape, because the yield in tonnes of fuel per hectare is much higher for wood. In addition, much less processing is needed to make wood into a useable fuel compared to the processing of oil crops or waste cooking oil.

If there’s a demand for bio-oils beyond what we can meet within the UK, then much more will be imported. This will push up production overseas – for example from palm oil – and the risk of environmental damage from deforestation.

Liquid biofuels (like biodiesel or bioethanol) were generally used for transport purposes in the UK because there was a financial benefit in doing so (due to tax rates – although this is no longer really the case). However, these biofuels don’t usually have any financial benefit over other, lower cost, heating options. Bulk vegetable oil or commercial biodiesel will both be much more expensive than heating oil.

Making your own biodiesel is an involved process and you’ll still need to get the raw material. This is not straightforward – waste cooking oil is generally now collected by companies that pay for it and do the relevant paperwork to show that they’re dealing with it properly. You’ll also need to invest in some modifications to an oil boiler to make it able to burn a biofuel (for some boilers, especially newer ones, this may not be possible anyway).

Given the cost of biodiesel, investing in a modern boiler able to (or even specifically designed to) burn this fuel will still leave high running costs, possibly up to twice as much as a heat pump or efficient modern wood-fired boiler.

Case study: Judith’s pellet boiler stove

Related Pages

Related events

Transformational International Energy Management

30th June 2025

Build a Small Wind Turbine

6th September 2025

Introduction to Renewables for Households

13th September 2025Study at CAT: Our Postgraduate Courses

Related news

More solar energy for CAT

4th April 2025

CAT Conversations – Dr Frances Hill

10th July 2024

CAT Stories – Aber Food Surplus

23rd May 2024

Taking back power

9th April 2024Related Books

Did you know we are a Charity?

If you have found our Free Information Service useful, why not read more about ways you can support CAT, or make a donation.

Email Sign Up

Have any questions?

Keep up to date with all the latest activities, events and online resources by signing up to our emails and following us on social media. And if you'd like to get involved and support our work, we'd love to welcome you as a CAT member.