As we transition away from an economy based on fossil fuels towards zero carbon there is the potential for the creation of hundreds of thousands of new green jobs. Anne Chapman and Jonathan Essex of Green House Think Tank explore the opportunities for areas across the UK.

The transition to zero carbon requires a different pathway for the UK economy. Investment is currently focused on the ‘growth centres’ and ‘powerhouses’ of our economy – primarily large cities – and it involves building more houses (often into the countryside) together with more roads and other infrastructure. To deal with climate change the powerhouses that we need to renew are much more human in scale – us!

Sufficient progress to address climate change requires a massive shift of investment from making our built environment and infrastructure ever bigger to making the buildings that we already have more energy efficient, installing renewable energy systems and electric vehicle charging points, improving local public transport, improving resource efficiency through repair and reuse of goods as well as recycling, and reestablishing local food economies that connect urban areas with their rural hinterland. All these will create jobs. Where will those jobs be, what will they be doing, and will they outnumber the jobs that will be lost in fossil fuel dependent sectors?

Modelling UK employment potential

Green House Think Tank has been working on this issue for a number of years for the Green European Foundation, building on the idea of a jobs-led transition put forward by the Green New Deal group and the One Million Climate Jobs pamphlet from the Campaign against Climate Change. We have developed a model to estimate the number of jobs in particular geographical areas. We looked at the Isle of Wight in 2016, the Sheffield City Region in 2017, then in 2018 looked at the whole of the UK, split into the level three regions used by EU statistics (these put some district councils together). The findings are published in a new report: Unlocking the Job Potential of Zero Carbon.

The model sets out a ‘vision’ of what needs to be achieved in each sector; for example, the reduction in miles travelled and modal shift from private car to public transport (for which we drew upon CAT’s Zero Carbon Britain reports), or the number of dwellings fitted with solar photovoltaic systems or heat pumps.

It takes available information about the numbers of jobs associated with the different elements of this vision – installing renewable energy, insulating homes, recycling waste, producing food and increasing public transport – and combines it with data on local areas, such as population, numbers of dwellings, waste production, travel, and land use to produce an estimate of the number of jobs that could be created in each area. An estimate for jobs required to train and support people to take up the new jobs was then added to the total.

Where information was available, the jobs that would be lost (for example in coal fired power stations or in maintenance of internal combustion engine vehicles) were subtracted from the numbers that would be created.

The resulting job numbers are likely to be underestimates because for lots of activities that will be part of the transition, upgrading the electricity distribution system and providing the battery storage needed for an all-renewable supply, no information could be found on the hours of work involved, so estimates could not be made.

Transition and long-term work

The total number of jobs created in the UK during a transition phase (up to 2030) was estimated to be 980,000, with 710,000 long term jobs thereafter. Most of the transition jobs are in the installation of renewable energy systems and in the retrofit of buildings (300,000 jobs each). There will also be lots of jobs in completing electrification of the railway system and installing electric vehicle charging points, but no data on these was available so estimates could not be made.

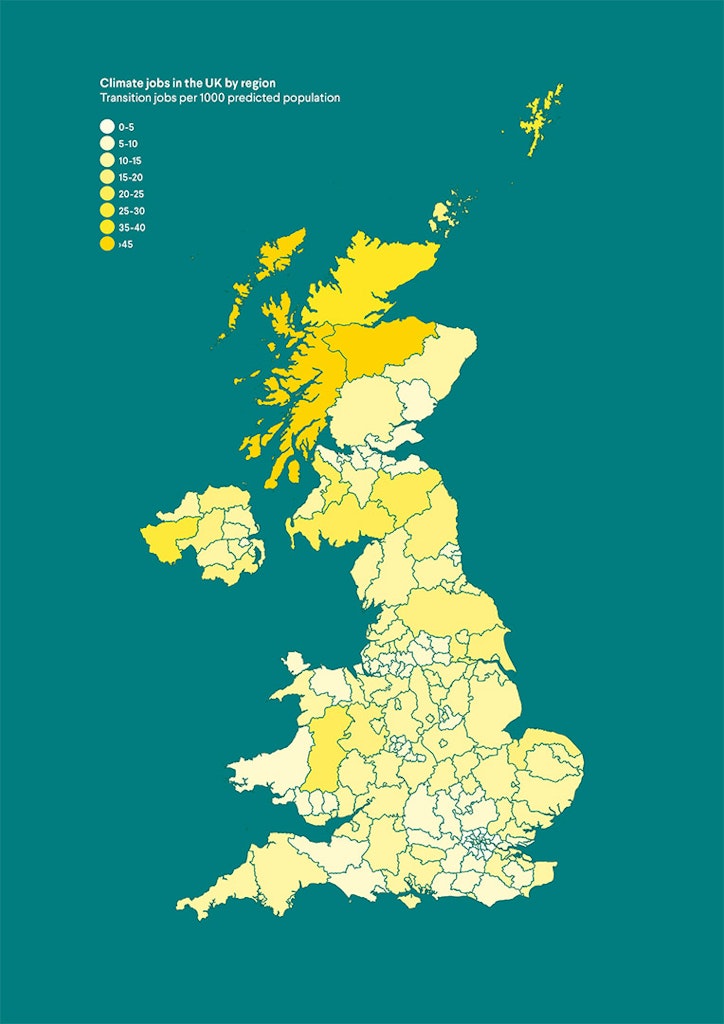

Long-term jobs are primarily in public transport (360,000), maintenance of wind turbines (100,000) and reuse/recycling of waste (84,000). The numbers of jobs per head of population are shown in the figure above. These jobs will be distributed all over the UK, bringing vitality back to our rural economies and small towns rather than being concentrated in large, already prosperous cities. Realising this will require a transition strategy that prioritises these local jobs: small scale renewable energy, not just off-shore wind farms; a programme of street by street retrofit of buildings in every community; supporting local businesses that reuse and repair goods; mechanisms to support agriculture that help farmers

provide permanent jobs, not just short-term seasonal work; good local public transport and live-work communities rather than commuting on high speed long distance trains; electric vehicle charging points in rural areas, not just in towns and cities.

This will require a different spatial plan for development of the UK, linked to a national climate jobs and industrial strategy. We also need to re-orientate our agricultural system so that it is ecologically sustainable; producing food for the UK population without contributing to climate change while reversing the decline in wildlife and soil nutrients seen in the last 70 years. Such a strategy would strengthen the links between the rural economy and our urban areas, potentially with more local mixed-use agriculture, and more wildlife friendly and productive woodland

management, increasing biodiversity and biofuels at the same time.

Resource efficiency

Investment needs to be employment intensive rather than carbon-intensive. While there will be some need for new energy generation and local transport infrastructure, there will be a lot of jobs created making better use of what we already have – more energy efficient buildings, improving ‘resource efficiency’ through reuse and sharing, and a reconnection with local food and the rural economy.

One of the authors of the report, Jonathan Essex, said:

“Our research shows that the transition to a zero carbon economy could create more jobs in ways that localise our economy across the UK. This is good news. But it also illustrates the scale of the challenge.

“Alongside the jobs in our plan there needs to be an industrial transition, shifting from making fossil-fuel dependent products to those needed by a zero carbon economy: for example from internal combustion engine to electric vehicles.

“Workers in these industries and those in fossil-fuel dependent sectors who will lose jobs need to be given the training and support needed to take up the new jobs.

“Making this happen requires local leadership to create the plans and new enterprises that deploy the skills and expertise of people in the UK. Achieving it would result in stronger, healthier and more locally sustainable communities.

“Only by working together in such ways can we truly do our part in tackling climate change.”

For example, consider just one of these job-intensive sectors: waste. We envisaged a reduction of 90% in waste going to incineration and landfill, through waste reduction, reuse and high-quality recycling. This could be encouraged with the establishment of a whole range of enterprises at the local scale, which are being set up in many places following the public awareness of plastic waste. There are a growing number of Repair Cafés and Men-in-Sheds projects (a community fix-it centre that addresses social isolation) as well as sharing initiatives such as a Library of Things alongside established projects to reuse second-hand furniture.

But why not extend this to construction and demolition, and re-popularise the notion of salvage and reuse surplus building materials from construction sites? This would sit well with the introduction of carbon taxes, which would make repurposing and reuse of products more viable economically – for example, reuse of cardboard boxes, or repair of small electrical items. This then creates possibilities for new jobs, using the recycled materials and retailing the reconditioned or repurposed products. In addition, there will be jobs in redesigning products so that they are more durable and more adaptable.

Unlocking the potential

The report on our 2018 work, Unlocking the Potential of Zero Carbon, is available on the Green European Foundation website. It includes estimates of jobs in Ireland and Hungary as well as the UK. The main report explains our methods and assumptions with summaries of the results while an appendix, downloadable as a separate file, gives the results for each UK area.

We acknowledge that there is scope for improving our modelling by improving accuracy and reliability of existing modelling and by filling in gaps in the jobs metrics. We would welcome constructive feedback on our work, especially from those who could provide additional sources or suggest changes to our modelling assumptions.

This year we hope to improve our model and produce summary sheets for local areas of the UK. We are also working on jobs estimates for Poland, with support from Fundacja Strefa Zieleni and the Institute of Eco-development in Poland.

Making plans for a zero carbon economy is the next step following the declaration of a climate emergency by many local councils across the

UK. You can find out more about how to do this, and hear about our work on climate jobs, at our ‘Climate Emergency, Raising Ambition’ conference in London on 14th September, where CAT’s Zero Carbon Britain project coordinator Paul Allen will also be speaking.

Click here to find our more and book your place

About the authors

Anne Chapman has been involved in the environmental movement for over 20 years. She is the author of Democratizing Technology, published by Earthscan in 2007. She is currently a director of Green House Think Tank.

Jonathan Essex is a chartered engineer. He has worked for engineering consultants and contractors in the UK, Bangladesh and Vietnam. His current work focuses on improving the sustainability and resilience of livelihoods and infrastructure investments worldwide. He is also a Green

Party district and county councillor in Surrey.

Find out more

Unlocking the Job Potential of Zero Carbon; Report on the case studies United Kingdom, Hungary and the Republic of Ireland, by Anne Chapman, Jonathan Essex and Peter Sims. It is produced by the Green European Foundation with the support of Green House Think Tank and with the financial support of the European Parliament to the Green European Foundation.

Green House Think Tank publishes reports and organises events to promote the development of green thinking in the UK.

The Green European Foundation (GEF) is a European level political foundation funded by the European Parliament. Its mission is to contribute to the development of a European public sphere and to foster greater involvement by citizens in European politics.

- Zero Carbon Britain

- Climate Change

- Energy

- Building

- News Feed