Reducing the amount of energy we use to heat our homes is one of the key ways we can tackle greenhouse gas emissions. Joel Rawson looks at the role of airtightness and ventilation in creating comfortable, energy efficient buildings.

Reducing heating demand is key to a zero carbon future, because it’s then far easier to install enough renewable energy to meet the remaining demand. Upgrading insulation makes the biggest impact, but air infiltration also causes significant heat loss.

In CAT’s ‘Zero Carbon Britain: Rising to the Climate Emergency’ report we recommend building new homes to the ‘Passivhaus’ standard or similar. That means stringent airtightness and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR).

We also recommend a mass refurbishment of existing buildings. A whole house retrofit may well also lead to using MVHR to give good indoor air quality, but in some cases passive (nonpowered) ventilation, or a mixture, may be enough.

Unintentional vs intentional ventilation

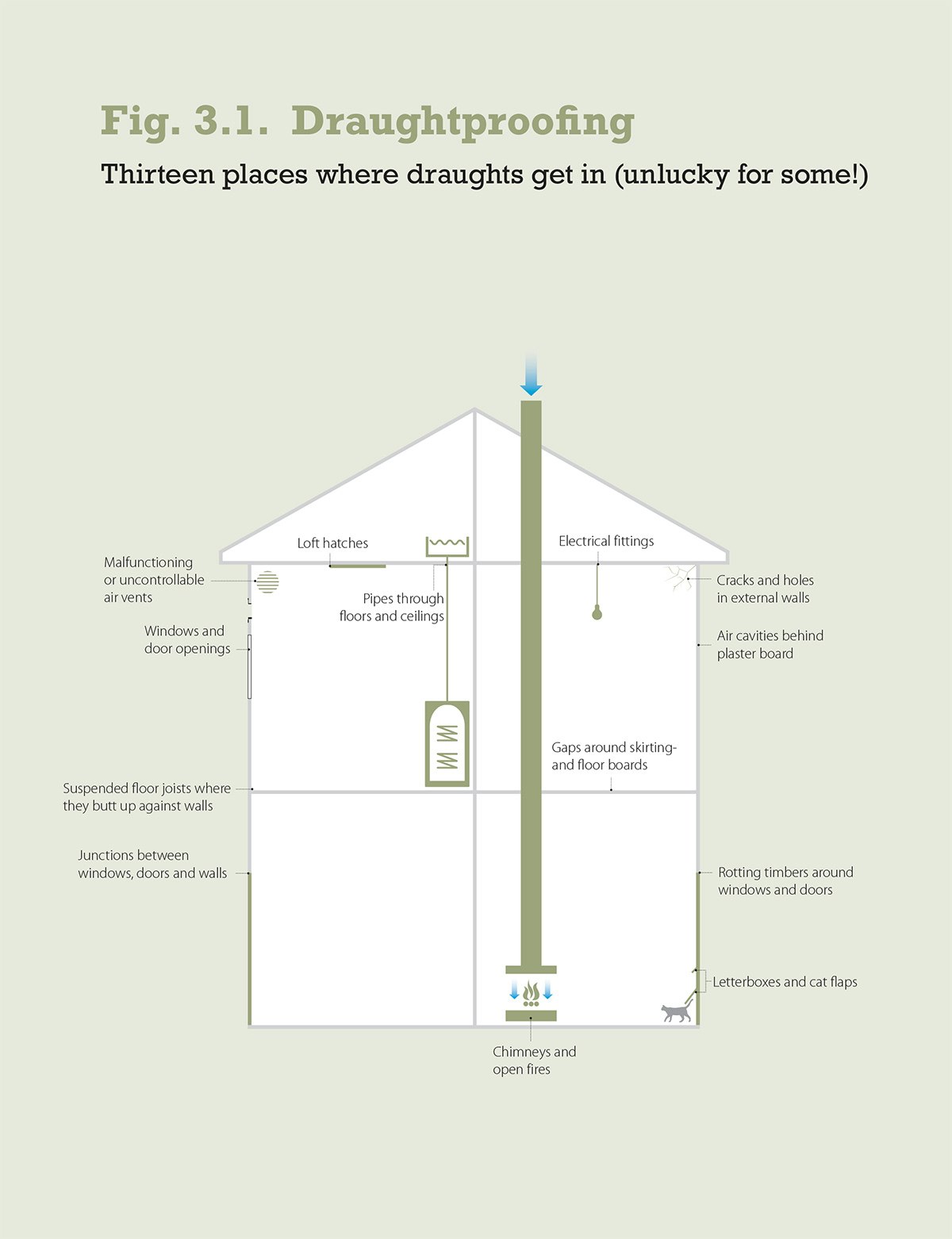

‘Build tight, ventilate right’ is a longstanding energy efficiency mantra. The aim is to stop unintentional ventilation and instead provide intentional ventilation. Airtightness applies to the entire building fabric: gaps and cracks at the corners and edges where materials join, holes for pipes and cables, where joists penetrate a wall, and so on.

The benefits go beyond energy savings. The right approach to airtightness actually makes a house feel both fresher and more comfortable. The thermostat tends to be cranked up in a draughty house to counteract the cooling effect of incoming air flows. In contrast, with low air movement a home remains comfortable at a lower temperature.

With good airtightness, effective ventilation replaces stale air – including carbon dioxide, cooking smells, water vapour, dust, off-gassing (for example from new appliances), and so on. If a building isn’t airtight enough, planned airflows for some types of ventilation won’t work as intended.

In addition to draughts, ‘thermal bypass’ can cause further heat loss. This is when outside air gets past the insulation layer and into spaces within the building fabric. The ‘dot-and-dab’ technique for quickly fitting plasterboard creates voids prone to thermal bypass. It also happens when spaces in a roof or intermediate floor aren’t properly sealed when being insulated. As well as heat loss, these cold patches are at risk from mould growth.

Measuring airtightness

The first step is to know your starting point by having an airtightness test. Then you can set a target for improvement and a strategy to achieve it.

Airtightness in older buildings varies a lot, and you can’t tell just by looking. Using thermal imaging during a test helps to identify heat loss from air leakage, by comparing cold spots visible during the test to those when unpressurised. A local energy agency or community organisation may be able to provide an initial survey.

A blower door test shouldn’t be very disruptive or expensive. Existing ventilation points like extractor fans, trickle vents, and flues are sealed. A powerful fan extracts air to create a pressure difference that amplifies air infiltration, allowing you to measure nonintentional ventilation. You may want the

test to give two measures:

- Air permeability relates to the surface area of a building. It’s used in UK building regulations. The units are cubic metres of air per hour per square metre of surface area: m3/h.m2@50Pa (tested at 50 Pascals pressure).

- Air changes per hour (ach) relates to the volume of a building. It’s used in high standards such as Passivhaus (1ach@50Pa for retrofit) and AECB retrofit (2ach@50Pa).

These could be very different, especially for a less compact layout with a high surface area. When speaking to contractors make sure you’re both talking about the same measure.

Aim and strategy

Once you have a baseline, you can decide on an airtightness target that is practical for your project, considering also the type of ventilation you’ll then need.

A typical modern house probably has an air permeability of about 5m3/h. m2@50Pa. Some older homes are similar, but many are much leakier.

Recommendations vary, but for mechanical ventilation to be appropriate you’ll probably want less than half that. However, MVHR proponents say that the dedicated air intake means it saves energy even if airtightness is only to a reasonable level.

To deliver a more exacting target you need an airtightness strategy. This specifies where the airtight layer will be, with details for all the junctions, gaps and holes. When going for a tested standard, set your target to give a bit of margin for error.

Hitting the target

Make sure that the target and strategy are clear to your architect and builders, because effective ventilation depends on it. Because attention to detail is vital, you need a good relationship with contractors and they must be fully engaged with the process. Stringent airtightness is still new to many in the UK, and having a ‘no blame’ culture allows you to get mistakes fixed before it’s too late.

There are special tapes and grommets for sealing junctions and problem areas, such as where electricians and plumbers run pipes and cables out of the building or into an uninsulated loft. Other weak points include recessed lights and the loft hatch. For some older houses secondary glazing might be a less costly option than replacement glazing for getting the required airtightness at window frames.

Ventilation types

Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) extracts warm stale or moist air, generally from the bathroom and kitchen. A heat exchanger transfers the heat to incoming fresh air for other rooms. The filtering of incoming air is an advantage where outdoor pollutants are a concern. MVHR should have very low running costs, saving much more energy than it consumes. However, as a decent Passivhaus-certified system will cost a few thousand pounds, the retrofit must be to a suitable standard to make it worthwhile.

Ventilation that only extracts air needs very good airtightness and careful design to draw enough fresh air in to where it’s needed (through trickle vents or similar). In a well-draught-proofed house, passive ventilation depends for success on manually adjusting windows or other inlets as required. You can supplement a mostly unpowered approach with a small heat recovery fan for the bathroom (perhaps also the kitchen).

Pitfalls

Passive or mechanical ventilation can fail to deliver if there are mistakes in the design or installation or if it’s not maintained – resulting in a stuffy, humid and unhealthy house. A successful approach must work under normal living conditions, for example don’t rely on leaving bedroom doors open.

Poor design or installation of a mechanical system could make it noisy. Large diameter ducts and a low air resistance heat exchanger keep the noise and energy use of fans very low. Rigid ducting is preferable to flexible, which may be easier to install but tends not to perform well. In general, flexible ducts lead to more noise, are harder to clean, and don’t last as long. For heat recovery to work efficiently, the MVHR unit and ducting should be within the insulation layer, not in an uninsulated loft where they’ll lose heat.

Check the maintenance required to keep a ventilation system efficient and healthy, and that there’s access for this. For example, with an MVHR system you’ll need to check the filters every few months and clean or replace as necessary. Replacement paper filters might cost £10 to £15. You may need a more thorough servicing and cleaning of the heat exchanger and fans every few years.

Finding help

Getting good advice upfront should give big savings later. Local community based organisations are ideal as trusted intermediaries – bringing together householders and local tradespeople, and supporting both. At the moment, there are organisations like this dotted around the UK, with more gradually springing up. There are also bodies like the AECB (Association for Environment Conscious Building) and Passivhaus Trust that list professionals trained to high standards.

About the author

Joel Rawson is CAT’s Information Officer, providing free and impartial advice on a wide range of topics related to sustainability. He first came to CAT to volunteer in 2001, and graduated with a CAT Postgraduate Diploma in 2013.

- Zero Carbon Britain

- Building

Related Topics

Email sign up

Keep up to date with all the latest activities, events and online resources by signing up to our emails and following us on social media. And if you'd like to get involved and support our work, we'd love to welcome you as a CAT member.