This year sees world leaders meeting in Poland for the COP24 climate change talks. Paul Allen explores the background to the talks, and what needs to happen next.

The United Nations climate negotiations are probably the most important series of meetings in the history of humanity, yet the process remains distant for the vast majority of citizens. Whilst many people are aware of the target agreed in Paris in 2015, it’s hard to get to grips with how well we are doing in delivering the levels of ambition needed. There is little mention of the talks in the mainstream media, hardly any news coverage, no documentaries or celebrity experts explaining to us how it works and what is happening.

However, it is now crystal clear that the most vulnerable are already suffering terrible consequences from an increase in extreme weather events. If humanity does not get to grips with the climate negotiation process we face the biggest threat in our entire history.

The talks so far

Initiated by the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) came into force on 21st March 1994. It sets out the overall framework for bringing together efforts by the world’s governments to tackle the serious challenges posed by climate change. It gained near universal acceptance, with the 195 countries that signed-up being referred to as ‘Parties to the Convention’. Since then annual ‘Conferences of the Parties’ (COP) have been held to assess progress and agree the actions that need to be taken.

By the time COP13 came around, the stark urgency of the climate science triggered a two-year process called ‘the Bali Road Map’, aiming to finalise a binding agreement by 2009 at COP15 in Copenhagen. To support this process, I presented CAT’s first Zero Carbon Britain report at both COP14 in Poznan and COP15 in Copenhagen. However, despite a great many people pushing for a solution, Copenhagen failed to deliver any serious commitments. A ‘Copenhagen Accord’ was drafted by a small group of countries, but it was not based on the texts developed in the negotiations and was nowhere near adequate given the scale of the challenge.

Humanity learned a hard lesson when Copenhagen failed to deliver. A great many people became very disappointed and disillusioned with the UNFCCC process, but we had no option other than to press on. The process was re-thought, with a focus on agreeing the global targets at COP21 in Paris in 2015. Rather than having to reach a final agreement which apportions exactly who will do what, the Paris process was based around ‘voluntary pledges’ from each country, backed by a ratchet mechanism to increase ambition every five years, until the pledges become ambitious enough to deliver the targets.

To help ensure success, a great many diverse elements of global society came together in Paris to press for an agreement. Visionary leaders from both developed and developing countries, civil society, business, national politicians, the world’s major religions, citizen activists, celebrities, NGOs, mayors and governors all pulled together to push for an ambitious, binding agreement.

CAT was honoured to be invited to present Zero Carbon Britain at a couple of ‘side-events’ within the official Paris process. ‘Side-events’ are the way national delegations and research teams can access information from a wide variety of sources. This time success was achieved – a meaningful agreement around a target and a process emerged from Paris. This was an important milestone that revitalised confidence in the process.

The ‘Paris Agreement’ is a historic recognition that the climate science is now fully accepted by the vast majority of nations. Its mitigation target (called ‘Article 2’) turned out to be far more ambitious than many of us expected. This was due, at least in part, to the last-minute growth of a ‘high-ambition coalition’, voicing the passionate demand of many vulnerable countries. Article 2 states that signatories to the agreement must aim to “hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre- industrial levels, recognising that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change”. It sparked real hope that governments were serious about ambitious and collaborative leadership, working towards a world where warming would be limited to 1.5°C, so protecting many of the most vulnerable areas.

Do current pledges actually meet the target?

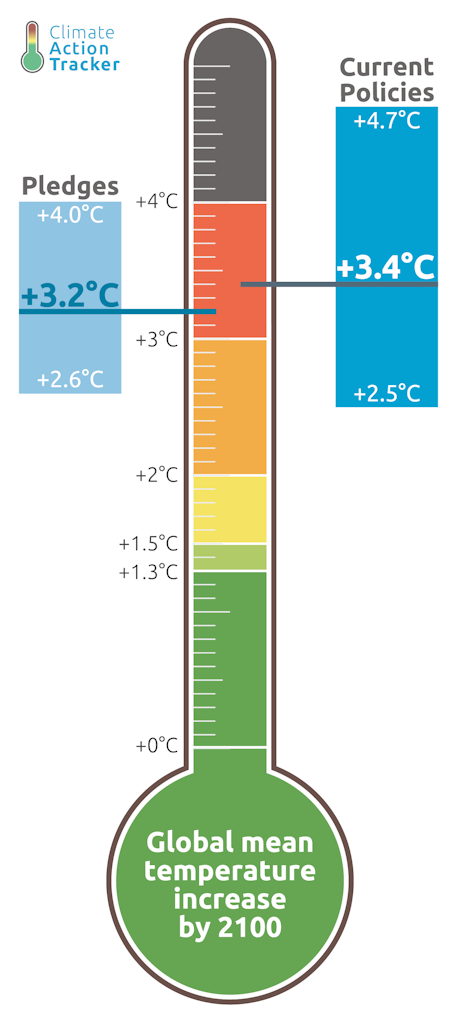

Unfortunately, there is far too little awareness of the scale of the gap between what our collective pledges currently offer and the targets agreed in Paris – and, following a potential US withdrawal, this gap could widen. Analysts from Climate Action Tracker estimate that if all other governments fully implement their Paris pledges but America does nothing there would be an average global temperature increase of 3.2°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. This marks a worrying rise on their pre-Trump estimates of 2.8°C from 2016.

In addition, after having levelled off for the past three years, the global carbon emissions now seem to be on the increase again. The Global Carbon Project (GCP) studies an integrated picture of the carbon cycle and other interacting biogeochemical cycles, including the human dimensions. During COP23, they announced an expected rise in global emissions of 2% for 2017. There are many reasons for this, but a significant one is that China has begun to burn more coal again.

Another sobering indicator is the 2017 UN Environment Emissions Gap Report. This shows that the gap between the existing pledges agreed in Paris in 2015 and the 1.5 and 2 degree trajectories for 2030 ranges between 11 gigatons (for 2°C) and a massive 19 gigatons (for 1.5°C).

The national action pledges that formed the initial offerings to the Paris Agreement currently add up to approximately one third of the total emissions reduction needed to be on a pathway for the goal of staying well below 2°C. If the end goals of the Paris Agreement are to remain achievable, there is an urgent need both for accelerated short-term action and enhanced longer-term national ambition.

The ratchet mechanism

Keeping global temperature rise to well below 2°C requires humanity collectively achieving net-zero emissions by around 2050. Fortunately, those who developed the negotiation process underpinning the Paris Agreement recognised that any initial climate pledges would be unlikely collectively to deliver against the target. The Paris Agreement therefore contains provisions to raise ambition over time through a ‘ratchet mechanism’, sometimes referred to as the ‘ambition mechanism’. This commits each country to submitting new action pledges every five years, each of which must be progressively more ambitious than the last.

The first test-bed version of this ratchet mechanism will happen at COP24 this December. The original name for this trial run was the ‘facilitative dialogue’; this was re-named the ‘Talanoa dialogue’ last year during COP23 under Fiji’s presidency. Talanoa is a traditional word used in Fiji and the Pacific to reflect a process of building empathy and making wise decisions for the collective good. As the emissions gap is significant, early action is needed to ensure that future rates of transition remain achievable. Increasing ambition as quickly as possible is vital.

The role of last year’s COP23 was to lay the groundwork for the Talanoa dialogue. Although hosted in Germany, Fiji’s presidency brought strong and clear majority world voices to the negotiations.

To help counter the challenges of US withdrawal, many countries made formal commitments to support the vital scientific research being done by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) through a multi-year pledge. COP23 also saw the adoption of the first-ever UNFCCC Gender Action Plan (GAP) and the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform. The very first page of the Paris Agreement makes it clear that governments must integrate gender equality and indigenous rights in climate actions.

Perhaps one of the most powerful pieces of COP23 groundwork was that a group of 19 industrialised countries announced the ‘Global Alliance to Power Past Coal’. This is an international coalition to phase out coal power, with President Emmanuel Macron declaring that France aims to close down all coal-fired power plants by 2021. Sadly, the major coal producing and using nations, such as Australia, India, Germany and the US, did not join.

Leadership, but not as we know it

One of the most important aspects of COP23 was the clear sign of a new kind of leadership emerging from many countries across the globe. States, regions, cities, businesses and civil society are simply pressing on with delivering. Although the Trump administration has given a cold shoulder to the spirit of Paris, shortly after COP23 opened I was invited to an independent pavilion entitled ‘The US Climate Action Centre’. In the absence of any federal leadership, communities and organisations from across the US opened a special pavilion to stand alongside the international community, making it clear that the US is ‘Still in for Paris’.

Such a pavilion is the very first of its kind and represents more than 127 million Americans and $6.2 trillion of the US economy. University presidents, mayors, governors, citizens and business leaders profiled the steps they are taking to reduce emissions. This bottom-up network is a clear example of the leadership emerging from areas across the globe in response to the urgent challenge of increasing ambition.

COP23 was a hive of new leadership, tens of thousands of people working 24/7 over two weeks, cross-pollinating ideas to fertilise ambition. It was reassuring to see that zero carbon is becoming a much more commonly used term. I was pleased that CAT received five invitations to present Zero Carbon Britain at official COP23 side-events, more than at any other UN climate summit to date. I collaborated with a wide range of partners, from Welsh Government to the Global EcoVillage Network, to share CAT’s positive vision. I also made a point of visiting the official Government and NGO pavilions to share our work, highlighting the increasing number of cities and regions, such as Edinburgh, Liverpool and Yorkshire, which demonstrate real leadership through declaring a local Zero Carbon goal. Showcasing detailed scenarios making it clear we have all the technical solutions, backed by a clear understanding of how to overcome the barriers, offers a vital tool to support delegates in increasing the ambition of their national commitments.

All hands on deck!

So, as the world prepares for COP24 in Katowice, Poland this December, we need to recognise that we are heading towards a pivotal moment in human history. Our collective challenge is to forge ambition among 7 billion people to rapidly change the way we inhabit the world. At COP21 in Paris it felt very much as if the world was watching, with events happening all over the city and all over the globe – COP24 requires a similar level of engagement. Active citizens need to increase awareness of the pledges their countries currently offer and press their governments for clear progress at COP24. All countries must enhance their pledges, and have their actions ready to begin in 2020.

CAT will be developing our Zero Carbon Britain work in the run up to COP24. We aim to begin exploring the factors that have contributed to the success of zero carbon initiatives across the world. Cities, regions, individuals, communities and businesses have amassed a wealth of experience. We shall begin to investigate what works, where and why, highlighting both the enabling factors and the co- benefits

Our next Zero Carbon Britain short course is scheduled for 2nd to 4th May – come join us!

This article originally appeared in CAT’s magazine, Clean Slate – become a member to receive your copy every quarter.